By Josie Thaddeus-Johns of the New York Times. Originally published April 26, 2019. Click here to view the article in its original format.

Daniel Birnbaum bet on VR when he left a prestigious museum to join a start-up. Is he a savvy pioneer or an evangelist for dead-end technology?

LONDON — When Daniel Birnbaum announced last summer that he was stepping down as the director of the renowned Moderna Museet to join a virtual reality start-up, it raised eyebrows in the art world.

After all, the Swedish curator was at the top of his game, working with some of the art world’s most prestigious institutions. In addition to the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Mr. Birnbaum had led biennials (including Venice, in 2009) and a prominent art school (Frankfurt’s Städelschule). He had been a jury member for the Turner Prize in Britain and organized countless contemporary art exhibitions.

Why would he leave all this behind to work with VR, a technology still in its infancy?

Daniel Birnbaum, who left his post at the Moderna Museet to join a virtual reality start-up. CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

Daniel Birnbaum, who left his post at the Moderna Museet to join a virtual reality start-up.CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

“It’s exciting because it’s a little uncharted,” Mr. Birnbaum said at the London headquarters of his new employer, Acute Art. “It comes out of my interest in what art and technology are all about. I think people expected me to take over another museum, in Germany. That would have been very normal.”

In an interview in February, only a few months after he took over the company’s artistic leadership, Mr. Birnbaum, 55, seemed relaxed and energized. From his office at Somerset House, a neo-Classical building housing arts spaces that overlooks the River Thames, he’s been overseeing Acute Art while also planning a new curatorial venture: a VR-focused booth titled “Electric” at Frieze New York, which runs May 2-5.

VR generally refers to high-resolution experiences that use a headset to place viewers in immersive environments. Video game developers have found commercially viable uses for the medium, and moviemakers have also dipped their toes in: Last year’s Venice Film Festival had a dedicated section for VR works.

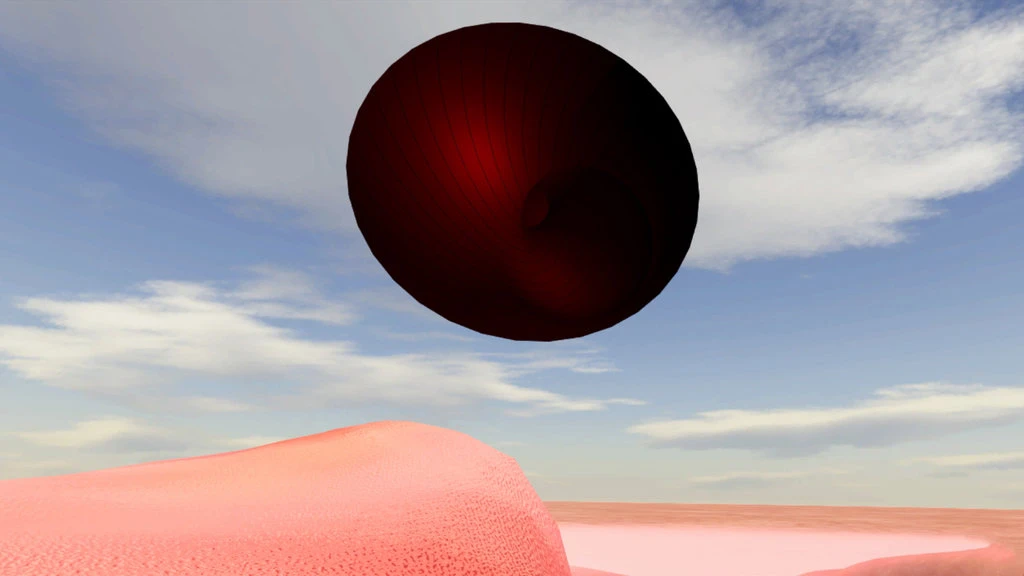

Experiencing Anish Kapoor’s “Into Yourself, Fall” (2018).CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

And slowly, cautiously, virtual reality has made its way into the contemporary art world, too, with biennials and art institutions presenting works that come to life inside those big black goggles.

Viewers have lined up in response. For example, Jordan Wolfson’s “Real Violence” caused a stir at the 2017 Whitney Biennial with its graphic depiction of the artist brutally attacking a stranger on the street; at the Berlin Biennale in 2016, Jon Rafman’s “View of Pariser Platz” showed the famous Berlin square being swallowed by an apocalyptic explosion.

While many creators are excited about VR’s possibilities, the technology to realize them has some problems. Remaining in the immersive environment for too long can induce a nausea akin to vertigo — “virtual reality sickness,” it’s been called. While there’s plenty of investment in both software and hardware, the headsets are still aimed at the gaming market. It’s still not clear how audiences outside that niche will get access to the full VR experience without shelling out for a pricey headset.

Image

Mr. Kapoor’s “Into Yourself, Fall.”CreditAnish Kapoor; Acute Art

Stepping into this volatile landscape, Acute Art sees itself as something between a production company and an artist studio. Dedicated solely to creating works of contemporary art, it started out with a roster of world-famous artists who were completely new to the medium: Anish Kapoor, Jeff Koons and Marina Abramovic have all since made their first VR works with the company.

For his Frieze New York booth, Mr. Birnbaum has selected several works produced by Acute Art, such as Mr. Kapoor’s “Into Yourself, Fall,” a stomach-churning plunge through the viewer’s own body into a kind of afterlife, and a new work by R. H. Quaytman that responds to the mystical paintings of the Swedish artist Hilma af Klint. Mr. Birnbaum said it was also important for him to include artists whose work wasn’t produced by Acute Art, like Rachel Rossin — an outlier in the field because she does all her own coding.

Mr. Birnbaum said he was aware that these might be the first VR art experiences for some in the Frieze audience. “For the normal art world, it’s a novel thing,” he said. “I hope this will create curiosity.”

From Rachel Rossin’s “Man Mask” (2017).CreditRachel Rossin

Image

Acute Art reinvents the production process for each work it produces to suit the artists. The piece by Ms. Abramovic, for example, demanded a highly detailed, three-dimensional avatar of the artist herself, which the viewer can choose to save from rising sea levels; Mr. Koons wanted a metallic ballet dancer whirling around an ornamental garden.

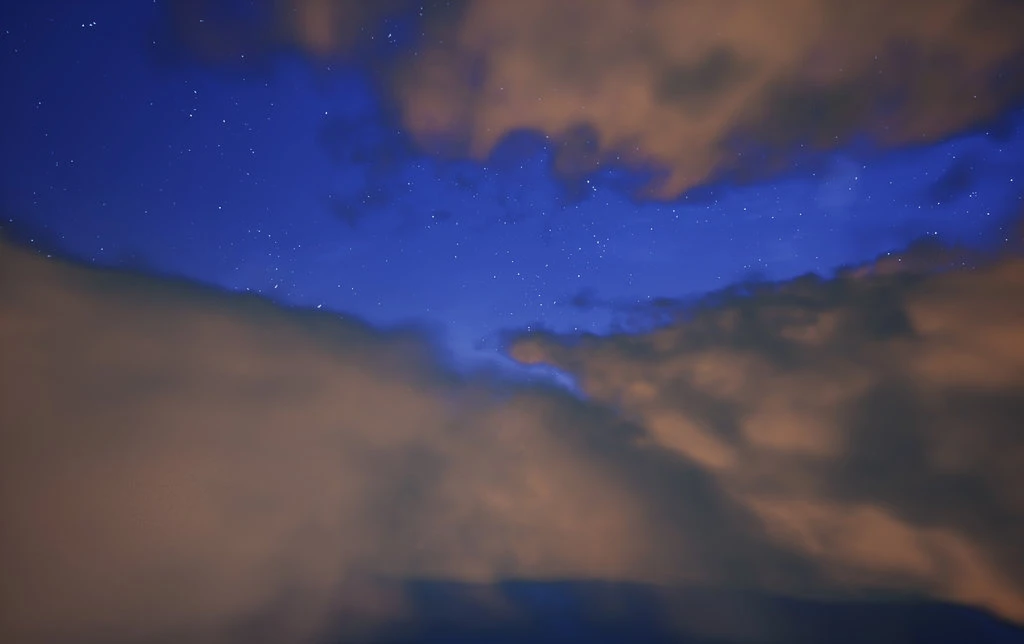

This means that the studio setup changes with each new work: One week, a row of computer screens showed clay animals that team members were digitally animating; the next, they were modeling NASA data to recreate outer space for Antony Gormley’s “Lunatick,” a work produced in collaboration with the astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan.

The mastermind of Acute Art’s technical output is Rodrigo Marques, the chief technology officer, who works closely with artists. On a visit to the office in February, Mr. Marques was overseeing the programming of Mr. Gormley’s piece, using design and animation software to recreate the environment of space as realistically as possible, as requested by the artist.

The piece begins with the viewer alone, exploring a remote island, before zooming into the atmosphere and landing on the moon. There, the viewer can wander in low-gravity across reproductions of the cratered surface. Making this technically feasible calls for massive amounts of information to be processed in milliseconds. “The amount of visual data required to simulate space is huge,” Mr. Marques said.

From Antony Gormley’s “Lunatick.”CreditAntony Gormley; Acute Art

From Antony Gormley’s “Lunatick.”CreditAntony Gormley; Acute Art

“For each artist, you need to figure out exactly what’s the best way to work with them,” Mr. Marques said. “It’s challenging.”

For a 2017 work by Olafur Eliasson, the Acute Art team created an uncanny reproduction of a waterfall with a realistic rainbow shimmer. (It was a nightmare to build, Mr. Eliasson said.) The Berlin-based artist is used to working with digital technology, and has employed at least one programmer in his studio since 2008. Mr. Eliasson said that the experience of working with Acute Art opened up new technical possibilities: “The level was way beyond what I would normally have access to,” he said in a telephone interview.

Although tech companies, including HTC Vive, Oculus and Google, are also working with artists to create VR works, they often have a more commercial attitude, Ms. Rossin explained. “They’re used to how advertising works,” Ms. Rossin, who is based in New York, said in a telephone interview.

But Acute Art, Mr. Eliasson said, was solely interested in making art that suits the artist.

“They fundamentally wanted it to be the best possible art work,” Mr. Eliasson said, “and the technical solutions had to fit to that.”

High-grade technical solutions don’t come cheap, and yet no money changes hands between Acute Art and the artists they work with. Instead, the company is funded by Gerard De Geer, a Swedish businessman and art collector, and his son Jacob. The company’s original business model involved making the works Acute Art produce available to headset-owning subscribers for a monthly fee, but the pay wall was dropped in June 2018.

Image

An Oculus Go VR headset.CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

Image

A cardboard VR viewer with a phone using the Acute Art app.CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

Now the company’s focus is on reaching a wider audience by way of the Acute Art app, which offers 360-degree video versions for free. These are less immersive than a headset experience but can be downloaded by anyone with a smartphone. The app also offers variations that works with Google Cardboard VR viewers, which use special lenses to create a 3-D effect.

“We are keen on having the largest outreach,” said Irene Due, the communications director of Acute Art. “If our aim is to get the biggest outreach, you have to make it free.”

Essentially, the business is betting on the artistic value of their products translating into commercial value down the line, presumably through a traditional gallery model of selling a small number of limited editions, although the company’s representatives were vague about their long-term strategy. “Our focus is to develop the works at this stage,” Ms. Due said.

Mr. Birnbaum said that one of VR’s biggest challenges is how to show it to large audiences. Until headsets are widely available, Acute Art is making do with phone-ready 360-degree video, or it is relying on gallery and museum shows where headsets can be provided.

At Frieze, Mr. Birnbaum has chosen to show simplified versions of all the works he is presenting, leaving out audience interactions so that more people can watch them: Viewers will be able to move around the virtual worlds, but won’t be able to have an effect on their environment. Engagement takes time to explain to the viewer, and that slows things down.

Image

CreditBen Quinton for The New York Times

But does this show the best of what VR can do?

That is just one of VR art’s many unanswered questions, and Mr. Birnbaum raised some more: “How will this be shown? How will it be collected? Will it at all be sold?” He seemed comfortable to leave these unresolved for now, but he acknowledged the future was uncertain.

“I hope I won’t regret it,” he said of his move to VR. “I don’t yet.”

A version of this article appears in print on April 27, 2019, on Page AR26 of the New York edition with the headline: The Man in the Virtual Mask.