Originally published April 13, 2019 by Dean Takahashi of Venture Beat. Click HERE to view the article in its original format.

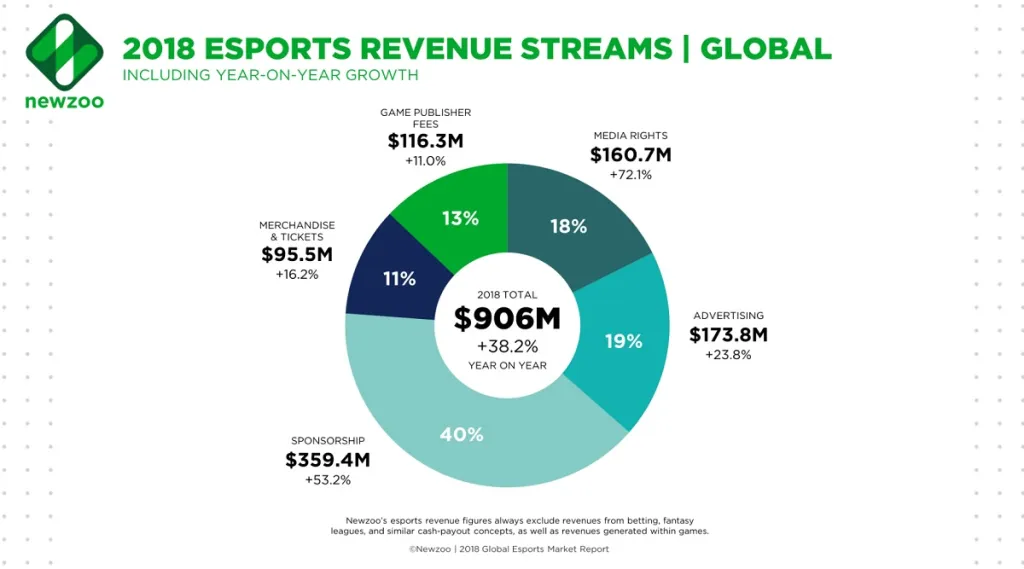

The world of sports entertainment is changing, and esports is the star player. Market researcher Newzoo forecasts that esports revenue will grow from $906 million in 2018 to $1.7 billion by 2021.

In an esports panel at the National Association of Broadcasters convention in Las Vegas this week, we explored how esports will disrupt the traditional notions of sports broadcasting. Esports broadcasts are evolving into something entirely different and much more interactive than what we’ve seen in the past.

We started at a high level, describing for non-esports fans what it’s like to enjoy a big tournament, and we moved on to the different ways it will impact broadcasting, generate money through a diversity of revenue sources, and draw the attention of the biggest advertisers in the world.

I moderated the session. Our speakers included David Clevinger, senior director of esports and sports product strategy at IBM Watson Media; Matt Edelman, chief commercial officer at Super League Gaming; Frank Ng, CEO, Allied Esports Entertainment; and Joe Lynch, head of broadcasting at Electronic Arts.

We tackled questions like the difficulty of broadcasting a battle royale match, the growth of physical venues for esports, how technology can make esports more interactive, and comparisons to traditional sports, like how much revenue per fan esports generates versus the NBA (Hint: Newzoo says it will be $5.45 per fan per year for esports, compared to more than $50 per fan for the Golden State Warriors.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel. Disclosure: The organizers of the session paid my way to Las Vegas. Our coverage remains objective.

GamesBeat: I’ve been writing about esports for at least a couple of decades, ever since Dennis Fong won a Ferrari in a Quake tournament. In those days everyone asked why anyone would want to watch someone else play a game. What’s the fun in that? Do we have a present-day feeling about why this has taken off? Why have people decided this is a fun thing to do? Twitch has more than 100 million monthly active users now, all watching people play games. We’ll be talking about this in multiple sessions at GamesBeat Summit 2019, our event in Los Angeles on April 23-24.

David Clevinger: The interesting thing about Twitch—I think I read somewhere that the average session on Twitch is an hour and 40 minutes. When I was at AOL doing broadband streaming, we would have killed to get someone to watch for an hour and 40 minutes.

What’s interesting about esports, and competitive gaming overall, is that it’s a different interaction model. The reason why it’s so interesting and why people watch is that you’re not watching for the same sort of spectator value that you get from watching an NBA game or the NFL or cricket or what have you. I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve been on a regulation-size football field in the last 10 years, but I’ve played a lot of esports and played a lot of games.

Depending on the way you watch esports, you’re getting something different out of it. It’s opening up different opportunities. You’re playing with your friends, communicating with your friends. You’re watching a stream rather than going to an event in a venue. It’s a different interaction model around that game than it is around traditional sports, which have a much higher barrier.

Joe Lynch: There’s a related factor to your point, which is that we have a generation of people who’ve been playing these games for their entire lives. They watch people play and they think they can get to that point when they play themselves. If you watch an NFL game, there are very few sane people who believe they can beat Tom Brady, but when you’re home and watching Madden or FIFA, a lot of people think, “I could beat that guy.” If you read Twitter during these events, a lot of people think they could beat pro players.

That relates back to the fantasy of, “That could be me.” I don’t have a shot at playing on an NFL team, but I can play in this league. I can do this.

Frank Ng: Streaming is a global phenomenon. It’s not just Twitch. There are a lot of platforms in Asia. It’s super big in China. The key thing is interaction. Gamers now are used to the interactions that these streaming platforms offer. Interaction, on one hand, you could say it’s engagement, just like playing a game, but it’s more like an addiction. Once people get on, they can hit that like, or make a comment, or send an emote. They can’t stop.

We’re still in the beginning stages of this cycle. A lot of games are not properly set up to take advantage of streaming. But we’ve started to see in the past few years with MOBA games, Clash Royale, things like that, they’ve added these features, and that’s made the game’s life cycle much longer. We can expect more games to come to this market and it will continue to grow.

Matt Edelman: If you’re interested in esports, relatively new to esports, it will help if you think of esports as sports. Don’t think of esports as video games that are completely distinct from a traditional sports experience. As a result, put yourselves in the shoes of a player of a sport, whether or not you think you can go pro. Think about how much you enjoy watching other people play that sport, whether it’s really well or even really horribly. You still enjoy watching, still enjoy the experience of being entertained by people playing the sport that you like to play yourself.

Esports is the same. Gamers enjoy watching other people play the sport that those gamers have chosen to be passionate about, because it’s what they like to play. Every time you wonder why somebody would want to watch esports, why someone would want to engage with an esports team, why a broadcaster should focus on what’s happening in esports, just think about traditional sports. Think about the growth of media rights in traditional sports over the past several decades. Think about all of the things broadcasters and leagues have brought to the table to make consuming traditional sports exciting from a visual standpoint. Esports is in the same place, and it’s going in the same direction.

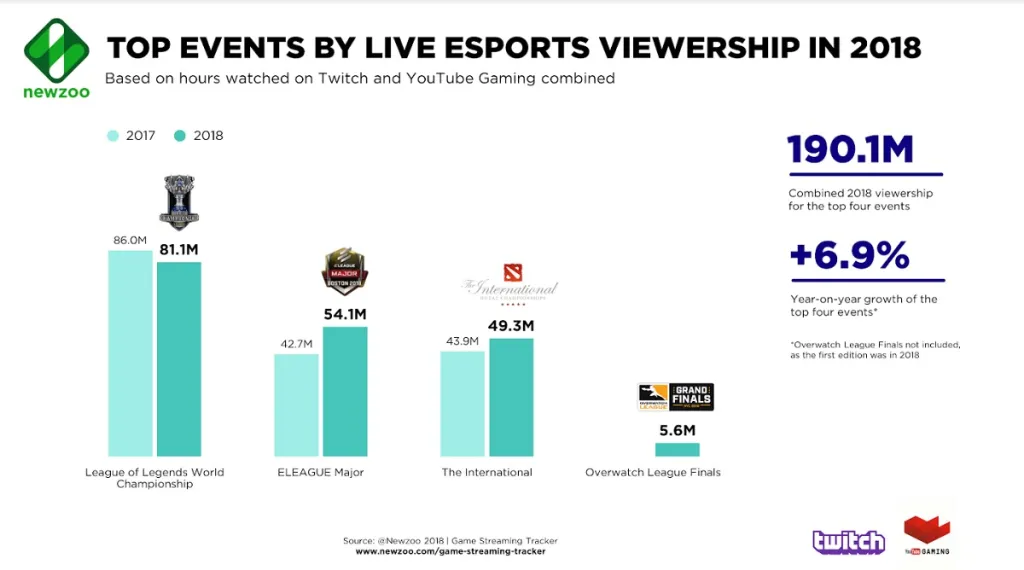

GamesBeat: There’s a market researcher, Newzoo, that’s studied esports for a while. They estimated in 2018 that the audience for esports was around 380 million people worldwide, if you add up both the enthusiasts and the occasional viewers. They think that will go to 557 million people by 2021. You could say, “No, I don’t believe that, that’s crazy.” But one streamer, a guy named Tyler Blevins, better known as Ninja, has more than 50 million followers across his different channels. He made more than $10 million off that audience last year alone. It’s interesting to add up how large this is, how real it is. The revenues for esports are bigger than things like WWE now. They’re not closing in on the NBA yet, but they’re legitimate sports.

I want to ask a bit more about the broadcast side of things. Joe, if you want to start, how is broadcasting esports different from broadcasting traditional sports?

Lynch: We look at it in a different way than some others at EA. We have our two big competitive games right now, Madden NFL and FIFA. The general public has an understanding of what those games are. We have a base to work from. We don’t have to explain what the game is and how it works.

But still, when it comes to technology and storytelling, there are two completely different worlds. As we were talking about, the reasons people watch, going by all these stats that we’ve looked at—the vast majority of the people who are watching are watching to learn. They want to learn how to get better. Millions of players enjoy these games and they’re watching to learn how to score more, how to run this play, how to do this thing.

As broadcasters and storytellers, we have to spend a lot of time teaching. NFL football games don’t do that. They’re not going to teach someone how to tackle. They’ll do a little to explain the basic rules so you can enjoy the game, but they’re not going to go into the minutiae of how you wrap someone up and tackle them. Those are the things we have to do as storytellers, and that part is really different.

We were just having a conversation earlier about the authenticity of it. As you’re telling the stories, you need people in the community, in these games, to be telling these stories, or it’s going to fall flat. No one’s going to enjoy it, because they know it doesn’t hold water compared to what the community is doing. That’s one side of it.

From the tech side, the signal flow is a mess. The way we’re getting signals out of the game – audio, video, shadow consoles – is by far the biggest difference. We have a lot of cameras. We have studio cameras, POV cameras, all that stuff that regular games have, but then we have all the game signals as well. We have all of that coming through, and that’s the most complicated difference between the two.

GamesBeat: In this case, too, the streamers are broadcasters. It hasn’t been that easy to be a streamer. You need one system to play a game and another system to stream it. That’s getting fairly complicated for people who are trying to make a living doing this at home.

Clevinger: Yes, there’s a big technology barrier to doing this, but it’s open. You can get the things you need and learn how to run the equipment. The bigger issue for streamers is that they have to do it every single day, for hours every day. If they take a day off and go do something else, they’re losing all that revenue coming in. A lot of people talk about what Ninja makes and what people pay him to do outside things. It’s because if he’s not streaming, he’s losing that money. The financial model is really interesting, and the commitment of time that these streamers have to put in to make it a viable career.

I do think there’s an interesting part of that where you can certainly make a correlation between how difficult it is to set up a box to go and stream—right now you have to have every platform you’re playing on, and then another box running a splitter, something like that. Then you’re sending it out to Twitch or YouTube or Facebook Gaming. There’s an opportunity to make that path much smoother, because the number of people who are streaming a game—regardless of the size of Twitch right now, that’s an increasable audience compared to the number of people that are playing games right now. That’s a much bigger audience. If you think Twitch is big now, and the game streamer audience is influential now, it’s really just getting started. We’re really in the infancy of that. It’s still complicated, but it’s not going to be complicated forever.

Lynch: As a developer, our teams are working on that every day. How do you make those tools easier? How do you press a button in a game and you’re good to go, so you don’t need to go through all of those steps? That’s a process that we’ll get to, but to your point, we haven’t even scratched the surface yet.

Ng: Last year we did a pilot after we launched our arena in Vegas, and we had Ninja there. At that time he was probably at one-third of his current popularity. He had maybe 4 million followers on Twitch. We did a six-hour show with him, and at the end we managed to pull off-peak concurrent viewership, just on his personal channel — we simulcast with our channel and his personal channel — of 680,000 users. After six or seven hours, we had 2.8 million unique viewers, again just from his personal channel.

In that process we also talked to a lot of sponsors. They come to us and say, “Yes, we love Ninja, he has a lot of great eyeballs. Streamers have a lot of great eyeballs.” But they want to structure something that’s more formal, more than just putting a logo on a T-shirt during a stream. That’s the big thing that we as broadcasters and content providers have to figure out. Can we utilize our attractiveness to bring much deeper content that can be consumed by a much bigger audience? That’s what we’re trying to do.

GamesBeat: We’re getting into the challenges of broadcasting esports as well. There must be a lot more of those.

Edelman: Another thing that’s unique about this category of sports—if you think about Major League Baseball, Aaron Judge is not broadcasting when he’s playing baseball. You can’t watch the Aaron Judge channel, or the Derek Jeter channel, even though he’s a retired player. That doesn’t exist.

In the streaming world, the choices that viewers have are almost infinite. There are viewers who would be just as excited, in some cases, to watch somebody they know, a friend of theirs, streaming gameplay, as they would be to watch a professional player in a professional match, and as they would be to watch a retired player who’s now a professional streamer and influencer. The importance of knowing how to connect with a viewer and capture their attention – and as Joe was saying, to convey a narrative that keeps their interest, whether it’s through a significant event like what Frank did with Ninja or grassroots events like ours that are happening in 20, 30, 40 communities around the country simultaneously in a given week – the storytelling is very new.

None of us have figured it out, other than knowing that you can get an audience when you have a great player playing and you have a publisher or a league presenting a professional match. We know you can get an audience for that moment. But knowing how you can get that same viewer the next day, the next week, with all the choices they have, is still a very complex ecosystem.

Lynch: To Frank’s point, airtime is a big difference between traditional sports and esports. We do anywhere from six to 10 to 12 hours a day for three to four hours a time, and then rinse and repeat a couple of weeks later. An NFL game is three hours, plus some pregame. You don’t have those kind of on-air hours. As you move from traditional sports to producing esports, when it comes to crews and TVs and directors and people you want to fill in your staff with, that’s a big learning curve, understanding what we do versus what traditional sports do.

Edelman: On that note, on airtime, that really speaks to volume, which goes back to what I was saying before about almost infinite choice. Over the course of the year, all the events that we run, we capture hundreds of thousands of hours of gameplay inside our platform. We’re running events based on other people’s intellectual property. We’re very fortunate that game publishers and developers have allowed us to create these programs with their IP, whether it’s League of Legends from Riot Games or Clash Royale from Supercell or Minecraft from Microsoft or Fortnite events in partnership with Epic Games and their sponsors.

Whatever it is, we’re accumulating an extraordinary amount of content. More content than any audience could possibly consume. It goes back to how you extract the right amount of value, how you figure out what the audience is going to be most interested in. How do you create the drama and the story that’s going to drive viewership, drive engagement, drive chat on platforms where chat is a key component of the experience? Twitch is the most noteworthy there.

Even the conversation about the speed at which things happen—maybe you have hundreds of thousands of hours of gameplay to draw from, but highlights happen in a matter of seconds, with almost no warning. It’s a very complicated broadcast and production experience.

GamesBeat: I spoke with a Los Angeles team, Gen.G, about the infrastructure they had to build to record video of a reality TV-like show for their League of Legends team. They needed a whole team of video editors just to be able to follow them at their house, watch them play, and take care of editing what was good to go on live and what had to be hidden. They’re in Los Angeles, so they had plenty of editors, but they couldn’t find people who knew about esports, and what content was important to the audience or not. That’s a huge human capital challenge right now, finding video people who know something about esports.

Clevinger: I would add to that, which is even that if you were able to find enough editors who know about esports, you’ll still never be able to churn out content as fast as you’d like to. It’s happening too quickly. Whether you’re talking about League of Legends or Madden or a battle royale type of situation, where you have players scattered over a map that’s miles wide and miles long, knowing where to focus and knowing what to extract becomes a really difficult problem.

Then you layer on top of that the fact that people aren’t just interested in players, but maybe I’m only interested in a character. If I’m watching Overwatch League, maybe I’m only interested in watching whoever’s playing Reaper. That brings on another layer of complexity. It’s not just about teams. It’s about the individual game characters.

GamesBeat: That gets to expectations of the spectators. They’re different from the passive viewers of the past. They want to take control of your broadcast and watch exactly what they want. They want to follow a specific player. If you’re not letting them take over that broadcast and do what they want, then they’re not happy.

Edelman: If you’re familiar with the game League of Legends, it’s a five-on-five game in the professional mode. You can think of it as similar to basketball. There are five roles, just like five positions on a basketball team. But imagine, at the beginning of a basketball game, that each team could decide which members of the other team are not allowed to play in that game. And they have to pick the positions and the people who are going to play on their own team for the duration of the game.

That’s what happens in League of Legends. A team decides, “You can’t use these characters for the whole game, and we’re going to pick the characters we’ll be for the whole game.” As a result, that part of the viewing experience is often as interesting and full of drama as the gameplay itself. Again, there are unique dynamics. Thankfully, there’s an increasingly exciting number of people who’ve been playing games for a long time, and in addition to playing games, have been producing video for a long time. They’re able to tell these stories. But the demand for this talent and experience is outpacing supply so far.

GamesBeat: Frank, you have different things to wonder about, like which games to pick and put into an arena, what’s going to work in a physical arena. Is battle royale going to work in something like what you guys have?

Ng: We try to be a platform provider. We try to create an ecosystem for every part of the industry. That’s why we’re building out our network around the world. This is just one of the many properties I have. There are others in China and Australia. We also have an esports broadcast truck. We have a lot of people who know how to organize esports events.

We try to take an agnostic approach. We try to work with everybody. We’ve worked with Riot, EA, Blizzard, and many other companies. At this early stage in the industry, we want to create content brands that are agnostic to any specific game. I was in the publishing business for 15 years, so I’m trying to do something different at this early stage of the esports business. I’m trying to be a platform provider, to create a different process we can go through.

Battle royale, to go back to that part, is actually a very good format. It’s just like poker. Anyone can be a winner. If you talk to any of your kids or nieces or whatever who play Fortnite, or any battle royale game, they’ll probably tell you that they’ve won maybe one, two, three times. Almost anyone will tell you that. It’s just like a poker tournament. You can play a thousand times and maybe get the big check once. It’s created a much bigger audience right now.

People may say that there’s a different way of creating content for the battle royale format, because you don’t have specific teams. Even with squads, it’s different. When we did the Ninja show, it was a battle royale game, Fortnite. It was before they even had the spectator mode. It was back when 20 players would go into the game and the first thing they do is shoot themselves and become ghosts to start following the big players.

The beauty of battle royale is that it brings a much bigger audience that can get engaged in the process. What we did with Ninja is we made him the center, the main character of the show. Unlike any other tournament–in a League of Legends broadcast you’ve got 10 people, five on five, so where do you want to focus your content? It’s hard. But for us, it was simple. It was just Ninja all night long, for seven hours. We had other big streamers, but they were all the supporting cast. Every moment was about Ninja. That’s why we could properly monetize his own channel’s traffic, and that’s why we could build him.

Battle royale is a great thing to appeal is a much bigger audience. Plus, battle royale is moving to mobile phones. Many games are offering that now. That’s really building the market.

Edelman: The idea of trying to figure out how to appeal to gamers–the reality is that most competitive-minded gamers play one game primarily, competitively. They play others, and they might get to be good at those games, but as far as where they focus the majority of their hours, where they’re grinding to get better and watching content to learn, it’s almost always around one primary title. That’s why, in Frank’s business and mine and others out there, the idea of being able to create a mechanism to allow communities to develop around multiple game titles simultaneously is very important, if you don’t own the games yourselves.

The way we do that is we run these locally-driven but national leagues and tournaments. We’re looking at communities like Las Vegas, where we created the Las Vegas Wild Cards team. We’re reaching out to Clash Royale players in Las Vegas, and we’re reaching out to League of Legends players in Las Vegas, and we’re reaching out to parents of Minecraft players in Las Vegas and so on. We’re bringing those players together. Sometimes digitally at first, but eventually we’re trying to bring them into a venue and help to create that connection between players.

That connection, which ends up leading to the creation of exciting content, is what’s starting to drive the growth of the industry. The way that players engage when they’re playing competitive video games together, in person, is just like what you would see in any other sport that comes to mind.

The positivity of gaming shines through when players are together in person. They get better at the game faster than when they play on their own. They don’t exhibit the kind of poor digital citizenship that you hear about a lot in online communities, where toxicity is a major issue. When players sit next to each other, they’re not toxic. They’re there to have a good time, to be friends, to form teams, to find other players they can learn from and play with on a continuous basis. That ability to create a platform across skill levels and across titles, particularly in visible locations, is a real driver of content creation and interest in content consumption.

GamesBeat: I want to get a bit focused on broadcast tools as well, and where technology could take them. There are a couple of recent examples, like where Twitch announced their Squad Play technology. Four players can join together and play a game like Fortnite as a squad there, broadcasting as a single stream. They don’t have to be in the same location.

Google has also talked about its Stadia cloud gaming platform. They brought up the example of a YouTube streamer who could be broadcasting a game, and you could click on a link to go into the game where that YouTuber is playing. Interesting developments can happen with technology. I’m curious about where you think broadcast tools for esports should go in the future.

Lynch: The main point is that there is no road map. With traditional TV there are lots of limitations on what we can do, how we can broadcast, how people can get involved, whether it’s in the living room or wherever. Right now we’re at a point where almost anything is possible. As long as you can figure out how to code it, you can do it.

We have a lot of conversations, whether it’s with Twitch or YouTube or our own dev teams or whoever makes these different games. “We have this crazy idea. What do you guys think?” To the point about what Twitch just came out with, the viewer wants to be in control. They want to be able to see what they want to see. They want to follow this person or that person. They want to enjoy their content their way. We want to do a really cool show that people will enjoy, but at the same time give them the opportunity to choose their own adventure, to do the thing that they want to do.

For me, it’s about how we can do whatever we want. It’s not so much what came out today. All that stuff is very cool, but it’s about, “Hey, we have this cool idea.” There’s a new battle royale coming out, and we’re starting to talk about what we could do to tell that story better. What could we take from traditional sports and combine with things that might not be available on traditional TV a couple of years ago, or even today? Because of the way things are working with Twitch and Facebook and YouTube, we can add on and plug in all these new things. The sky is the limit.

Edelman: We have a different challenge than Joe. When our events are happening in multiple locations around the country, simultaneously, we have dozens if not hundreds if not thousands of matches being played at the same time. The teen sitting in Topgolf in Las Vegas is interested in watching gameplay that’s relevant to them, while the teen that’s playing in a movie theater in Los Angeles wants to see gameplay that’s relevant to what they’re doing, and the teen in a Dave and Busters in New York wants to watch what’s interesting based on what they’re doing, all at the same time. We have a lot of those crazy ideas, and we have to challenge ourselves to figure out how to entertain viewers and players through all of those experiences simultaneously.

One of the really interesting things that esports has brought to life very quickly, in a way similar to traditional sports, is the use of all the data that surrounds the gameplay experience. The way our systems work, we’re broadcasting gameplay that’s unique to the players in each location, all simultaneously, and also broadcasting gameplay that’s interesting for a national audience on Twitch. While all of that is happening, yes, the gameplay is different for each distribution point, but so is the data that surrounds the gameplay, the data showing who is succeeding in each venue.

Who are the leading scorers in Las Vegas versus Los Angeles versus New York. Who are the leading scorers nationally, if you combine them all? What stage of the match are you in, if you’re in Los Angeles versus New York? All that data comes from partnerships with publishers who make that data available in different forms, through APIs or other mechanisms. Some of it has to be manual. But the ability to create that dynamic experience, for us, has become crucial. Otherwise, people in Los Angeles are watching gameplay based on players competing in New York, and that’s not fun.

GamesBeat: I’m sure IBM likes all that data.

Edelman: We’ve finally cracked one of the things that we’ve talked about elsewhere here, which is the redzone experience. If we have a team of 50 players in two different locations, there might be anywhere from 10 to 50 matches happening simultaneously. We can put five, six, seven, eight, nine matches up on the screen simultaneously. Multiple players can all enjoy a spectating experience on the match that they’re engaged in. Someone locally, in a venue, or someone centrally, in a control room, can bring any one of those matches up to be full screen at any point in time during the experience.

We were talking about how incredible it would be to be able to add highlights into that experience. While I call it the redzone–I’m not yet able to show you the most exciting point in each of those matches. I can just show you all of them happening at the same time. What if we actually could pull up, across five matches at once, the most exciting moments in all of those matches, and that’s what goes on the screen at a venue? It would be transformative. That’s where the access to data and the development of technology with companies like IBM can really take the broadcast experience to another level.

Clevinger: Some of the work we’ve done in the traditional sports space, and also other verticals as well, is pertinent to this. As an example, what we’ve done recently with the Masters, the golf tournament, which we also sponsor — we’re partners with Augusta — we were able to take in not just the match data, but also the audience, the crowd noise, and the commentators as well. We would run an analysis against all of that and generate an excitement score, based on how loud the crowd at the venue is, how excited the announcers are, and on the gameplay data. Whether we’re talking about traditional sports or esports, we can use that and know what is a critical moment in the match.

The thing I’m trying to build, that I’m trying to get to, is the excitement you feel when you watch the ESPN Sportscenter Top 10 at night. Somewhere in that mix is maybe a Little League match or a regional amateur event, but it’s always some fantastic experience that makes it into their top 10. What if that happened every day, all day long, in esports?

We’re talking about the ability to get to that, to make that correlation. Every event that Frank runs, every event that goes on in Super League, everyone who’s playing in a FIFA match, you can make a correlation between all of those things and start to create that sort of experience, which is above and beyond what we’re able to do with traditional sports, because they’re just harder to be able to break down. But with machine learning and being able to process that data, we’re building toward an inflection point where we’ll see the fruition of that. At the team level, at the publisher level, it’s going to create this groundswell. I’m sure we can figure out some way of bringing that to the in-venue experience as well.

Ng: I can also share some of the experience that we have. The one person who made poker broadcasting work is the person who invented the hole camera. Without the hole camera, there’s no poker on TV. We understand the importance of technology in the broadcast process.

That’s why we have different aspects to our platform. We have our handicap system that allows tournaments to take place and makes them more interesting. We also have streaming and simulcast features that we’re working with. It’s extremely important to focus on technology, because that will change the whole experience of watching.

I can share one fact that I strongly believe, which is that traditional broadcasters will play a different role in this process. In the future, there will be a single experience, with broadcast and live streaming on the internet, together as one unified experience that will be offered to the audience. Everyone has their role to play in this. But they should not be competing. They should be working together to create the experience that’s yet to come.

Clevinger: You have a recent example of broadcasting esports, right, with ESPN?

Lynch: Right. We just did a new series on ESPN called Road to the Madden Bowl. As we look at how we’re putting these events forward–we do a lot of live events, which are great, and we get a ton of viewership. What we’re trying to do now is tell more stories. As the viewership has grown year over year–the way we do that is get people invested in the players. You have to know who you love, who you hate, who you root for, who you root against. We’re creating shows and content, and you guys are as well, to drive that fact home and get people to understand who these people are.

Right now we have the Madden Championship Series, which is the full Madden 2019 series. We’re doing a four-episode series hitting each of the majors leading up to the Madden Bowl, which is going to air live on ESPN. The team at ESPN has been great about working with us and figuring out the best way to move this forward. We have what we’ve done traditionally, but now we have ESPN, ESPN2, ESPN News, Disney XD, all these other different venues. How can we pull all these levers and create something new?

To Frank’s point, part of what makes ESPN a great partner for us right now is understanding that we’re in the middle of a reinvention at the moment. What are we doing? Where are we going? What is this thing going to turn into? Companies like that are all in. “Let’s figure it out. Sure, we’ll try that.” Some people aren’t, and those people are going to be left behind.

GamesBeat: I thought it was interesting to compare esports and traditional sports when it comes to the revenue that comes in per fan. Newzoo has said that the revenue per esports fan in 2019 is going to be about $5.45. In a couple of years that’ll go up to $6.02. If you look at the NBA and a team like the Golden State Warriors–the average value of an NBA team, by the way, is $1.9 billion. The Warriors make about $50 per fan per year. The Cleveland Cavaliers make almost $90 per fan.

It’s an interesting contrast as far as showing us where esports is and how much potential it has to grow. The question is, how is it going to get there?

Lynch: You have to recognize some dramatic distinctions. One of them is, when you want to play basketball in your backyard, you don’t have to pay the NBA. When you want to get a new basketball, you don’t have to pay the NBA. When you want to get a new skin for your Fortnite character, you have to pay Epic Games.

A lot of those revenue-per-fan numbers, in my view, are not quite apples to apples. Fans of an NBA team–what they spend on merchandise from that team and what the team generates from that is potentially less than what a publisher generates from the player of a game. The question is, when it comes to esports revenue and looking that’s branded at the professional level, whether it’s the Madden league or the teams that are formed to participate in pro Madden competitions, and the players themselves who are on those teams and how their rights can be merchandised and monetized, I think those are where the comparisons make sense.

But there’s always going to be a big gap, in my view. I don’t think they’re going to end up being equal, because of the fact that players who are fans of esports are already spending a considerable amount of money just to play the game they enjoy.

Ng: The underlying element of esports is video games. Video games are the largest form of entertainment now, by far. They’re bigger than movies and music put together. Millennials, Gen Z, they’re used to paying for game content. But like I say, we’re still at the very early stage for esports as an industry.

Competitive gaming has been around for a long time, but as an industry we only started seeing media rights being sold by publishers to broadcasters in the past 18 months. We only just started selling the raw ingredient, the feed for the finals or whatever match you’re talking about. That’s a fundamental, basic element of selling content, and broadcasters still don’t fully know what to do with it. Maybe they get a poor rating on TV and they think it’s the game’s fault. Not true. It’s just not being processed properly.

For sports, one of the biggest chunks of revenue is media rights. The value is huge. It’s just that we need to create more formats, like what EA is exploring with ESPN. I believe that if broadcasters can come in with a different angle, rather than trying to replicate whatever they’ve done before with traditional sports, there’s a huge potential. This audience base loves to spend money on their games.

Edelman: What drives the value of media rights these days is advertising, and to some degree subscriptions to your sport of choice. But another thing that’s happening in an exciting fashion for all of us up here is the number of brands that are investing in money in esports now, sponsoring professional leagues and amateur programs like the ones we run, or venues like the arena here in Las Vegas. The more brands who get into the space, who choose to spend their money to reach esports viewers, the more we’ll evolve esports broadcasting.

Clevinger: We’re now starting to see a larger presence of non-endemic brands coming into the space. You mentioned the Golden State Warriors. Chase partnered to create a Warriors-branded esports team. They’ll have benefits tied to Chase credit cards and so on. It’s a great intersection of all of these things. The more non-endemic brands associated with the space, whether it’s events at facilities events around particular games–we’re going to see much more interest in the ecosystem. There’s a reason why these large brands and these large traditional sports companies are interested in esports. We’re going to see much more seriousness around getting non-endemic brands engaged with esports.

Lynch: Obviously we’re getting to see more people engaged and the cycle is getting bigger and bigger. The more advertisers come in, the more money that’s coming in, the more we get for production, the more we get dig into more technology, the more we get to do, which will help raise the bar for everyone. It’s really just the beginning now, with all the new brands coming in.

Question: My main focus around these things is digital objects. What are your opinions around this idea of creating a crypto platform where, setting all the cryptocurrency stuff aside, we can create digital objects like trophies, things that people can collect and so on? Do you see a future in that, and do you think that’s going to be a centralized economic model, like Epic Games selling skins, or do you think that’s eventually going to become a more distributed economy?

Ng: This is an extremely important element of games, this kind of item system. It’s critical. Because it’s so critical, every publisher feels that it’s their baby. If you start touching that, you have to be extremely careful in managing your relationship with publishers. They freak out. If you start to have any system like that touching Fortnite, for example, it’s going to be a very delicate situation. So the delivery and how you organize and launch that kind of thing is critical. But yes, gamers love this kind of thing.

Clevinger: As a company that has a blockchain solution like this that we’re launching next week–IBM blockchain works really well. We have multiple entry points into a longer chain of custody around a specific number of assets. That’s why it works really well for the food safety space, and we have a great offering around that. I think when you start getting into–if you think about Fortnite, Epic owns that game. They own the platform. There’s no loss of chain of custody in that asset. There’s no loss of chain of custody around who was playing and what they were playing. I’m not sure that a crypto type of offering can make a dent in the space.

GamesBeat: I thought it was interesting that Red Bull teamed up with Ninja to do a special Red Bull can with his face on it, but that’s a round of merchandise where we’ll see a lot of it. What if you had a single item, one item that was somehow associated with Ninja, and people could bid on it? What would that for? I think that blockchain and cryptocurrency would be the way to create that item and ensure that it’s truly authentic.

Clevinger: Yeah, but that lives outside the game space. Then you’re talking about creating an asset, something that literally is an asset. That’s a good use of blockchain. This thing exists. If you have an entire array of those types of assets, then there’s an interesting use of blockchain in that chain of custody scenario. But I don’t think that digital assets created by a publisher–I don’t think they’re that interested in using blockchain to validate those transactions.

Edelman: I don’t know how much this information relates to the viability of the crypto model here, but when Samsung got into business with Epic, they created a new skin, the Galaxy skin. Fortnite players could only get that skin if they bought a Samsung phone. There were people who bought a skin for $1,000.

Question: I’m interested in the gambling aspect of esports. I’ve been reading about a company called Unikrn, a gambling company. They’re not yet legal in the United States, but they’re operating in many other places. Now that we’ve legalized sports betting in the United States, the valuation of professional sports teams has skyrocketed.

GamesBeat: I know a bit about Unikrn. They can enable betting with cryptocurrency or with regular dollars on many kinds of matches. It’s skill-based, so it’s legal in 41 states. There’s another part of it, though, where they have to go outside the United States to enable various kinds of betting on different aspects. I can’t quite remember the distinction there. But as long as it’s skill-based they can run a gambling operation here in the U.S.

The game companies have long said that they don’t want to go there. They don’t want to go into gambling. There’s a distinction between entertainment and providing something that’s used for betting. It’s an opportunity for companies like Unikrn because the game companies don’t want to touch it. They don’t want to be associated with anything that minors could get into, or that could lead to addiction.

There are similarities in the relationships between other industries, like social casino games and real money casino games. But there are also some very hard lines, legal lines that have to be considered.

Lynch: Obviously our games, Madden and FIFA, are rated E for everyone. We have a lot of kids playing our games. To Dean’s point, this is not something we have any interest in getting involved with. From a sponsorship perspective, for instance, we don’t have alcohol sponsors or anything like that, because we have a lot of kids watching what we produce. So we have no plans, no road map to get involved with gambling at all.

Ng: For my part, we work with more than 50 casinos around the world. We just announced that WPT and Allied Esports have formed a partnership with the biggest sports channel in Mexico. That group also has a gambling license, so they ask a lot of the same questions. We hear them from casino operators around the world. It is happening, and it’s been happening for a long time with different games and different audiences, even if not all games are suitable for this.

There are publishers in the market that are looking to this, if not EA. They want to do it legally and they’re exploring that. It’s something to look into. In the future there will be a mature audience watching esports content who have a desire to bet on games. But I can tell you, to make that happen in a much larger way, the games will have to change. That match structure has to change. The kind of content will have to change. Then it can become much bigger than it is today.

Question: Where do you see adoption of virtual reality in esports? Do you see a timeline around that adoption?

Edelman: It’s not something that we’re engaged in, although there is a partnership that might come to fruition for us where we would get involved. The two most obvious challenges at the moment are, one, having the equipment available in enough players’ hands so that if you are bringing players together to compete, you can have a critical mass of players to make the competitive experience engaging and fun for everyone involved. The second is the game titles themselves. The games that are available using VR equipment are different games than the games that are driving so much activity and usage in the broader video game space and the competitive gaming space.

When you finally have enough players with the equipment, then you have to have enough of a subset of those players who are enthusiastic about a game that’s available through that equipment to develop enough of a competitive ecosystem for it to start to take shape as a meaningful component of competitive gaming.

Ng: The biggest technical challenge in that is you have to have a game that can be streamed properly. When you’re totally immersed in a game environment, you can’t control anything else other than the game. How do you stream in that situation? If that’s unresolved, you won’t have a lot of streamers pushing the games, and you won’t get any momentum.

GamesBeat: It’s very much a matter of incentives. I’ve seen esports tournaments around games like the Unspoken, from Insomniac, and Echo Combat, from Ready at Dawn Studios. But these are reaching very small audiences right now.

One thing that’s interesting is that Facebook owns Oculus. They’re more interested in social apps. They’ll do things like putting you courtside in a basketball game, letting people watch together from the vantage point of somebody who has the best seat in the house. If you do that for an esports event as well, that can be interesting. You might have a great view of the players and exactly what they’re doing. That could be very immersive in VR. There’s potential there, but as our panelists have said, the audience has to grow tremendously first.

Question: One of the differences you’ve talked about between broadcasting esports as opposed to other sports is the educational spin on it. I wanted to ask about something Blizzard did with the Overwatch World Cup, where instead of just watching through streams or typical broadcast channels, they let players log into the game itself and watch the games through the live perspective of a player, which felt like an entire new realm of interaction with a game. Is there anything you can share with us about technologies that can let viewers engage like that?

Lynch: That’s the fun part, right? That’s all the cool stuff we get to do. You heard me talk about Apex Legends, and that’s something we’ll be working on going forward. Working with that dev team to develop their spectator systems — what exactly that is, how that works, who can tap into that, and how they can follow the game. They can then either watch our main stream or watch individual streams or fly around and watch wherever they want. That’s the fun part.

Those are the kinds of things we’re working on right now. “Hey, I have this cool idea. Let’s figure it out.” Because we can. There’s no one saying we can’t. There’s no expectation that it has to be a certain way. With battle royale, all of us up here are still trying to figure out how to make it work, how to tell that story directly. To your point, really digging in to those technologies and those broadcast modes is what’s going to make it a lot more fun and unlock the ability for more people to get engaged with a game.

Edelman: On the one hand, every time a publisher brings new tools to bear, we are excited to be able to take advantage of those, up the broadcast experience, and tell better stories. Some publishers are really focused on it. Some publishers are focused a bit less actively. In those latter cases–we have two examples, one with Minecraft and the other with Clash Royale. We actually designed our own systems to be able to go into those games as a spectator and tell the competitive story in a different way than the publisher had decided to enable on their own.

Minecraft is not, by nature, a competitive experience. It’s the mini-games we create, and that are created by a lot of other companies, that make Minecraft competitive in a variety of ways. We created a spectator mode inside the games we run for Minecraft. That’s how we’ve been able to make that experience digestible from a viewing perspective.

Clash Royale is the same way. In order to broadcast Clash Royale and have five or six matches on the screen at once, we needed to figure out how we could get into the game client itself and extract the right visualizations in order to put that in front of spectators. From our perspective, it’s critical to be able to do that. So far, we’re very lucky that publishers have made those tools available and are continuing to make them available, or we’ve made the investment on our own in order to create a content experience that’s really special.

Clevinger: We’re starting to see the blurring of the lines between broadcast tools and the game engine. The division between those two things is going away. As tools are developed in Frostbite and the other game engines that are available, there’s not going to be–there’s absolutely going to be a move toward, how do we engage the audience with live streaming and VOD assets and other ways to create content through the game itself?

The Apex launch proved that. There was no preamble. There were rumors on a Friday that it was going to happen. All of a sudden people on Twitch were playing it, some of the big streamers, and it really took off. The dividing line between creating a game and building an audience around it with streaming platforms is completely going away. Twitch isn’t going anywhere. YouTube isn’t going anywhere. The overall consumption market for game streaming is going to get even larger than it is now.

Lynch: Now development teams are going into Twitch knowing that they’re going to need this down the road. Even at EA, our competitive division is only three years old. These games have been being developed a lot longer than that. Now these guys are looking at it and saying, “Okay, I get what you’re doing. This is what will be useful to you.” It gets a lot easier going forward. This is just going to be a part of the development cycle going forward, which will unlock a ton of new features.

Ng: Going back to what I said before, the hole camera was introduced on poker shows and poker became popular on TV. I can assure you that publishers will be inventing the equivalent of the hole camera for their games. Not necessarily just because of esports, but because this will bring through a lot more money for their games. They’re fully behind this. A lot of publishers are looking into this right now.