By Julianna Wu of Abacus News. Originally published April 1, 2019. Click here to view the article in its original format.

China might be one of the best countries for women in esports

Mobile games like Arena of Valor and tournament wins by Chinese teams like Invictus Gaming in League of Legends are drawing more women towards esports in China

This was the moment Siqi “Nara” Chen had been waiting for. When Invictus Gaming raised the Summoner’s Cup as the first Chinese team to win the League of Legends World Tournament, Chen felt her life was complete, having played the game herself since 2012.

“I was really lucky to be a fangirl there witnessing it,” said Chen, now 25, who previously competed as a professional player before becoming a tournament host.

Chen is part of a growing cohort of women gamers in the world’s most populous country. Once a rare sight, it’s no longer uncommon to see women players sitting in internet cafes or arcades. Women already make up a significant portion of the gamer market, making up 46% of gamers in 2017, according to data from Newzoo.

In an industry largely dominated by male players, China stands out for its gender balance in esports. The high penetration of mobile games and the increasing number of world championships won by Chinese teams, albeit all-male teams so far, is helping bring more women gamers into the fold.

Of China’s fans who have been following esports for at least four years, 30% are women, according to a Nielsen survey. China is second only to South Korea, where 32% of fans are women.

Although nearly a fifth of China’s esports fans started tuning in between 1998 and 2008, half of China’s female fans have only been following esports since 2017, according to Penguin Intelligence.

China’s strength in mobile might help give it an edge in attracting more women players, as women have traditionally favored mobile games over those on other devices. Nearly half of China’s esports revenue comes from mobile games.

“Our data shows that females in China are more likely to follow mobile esports titles than males, in particular Arena of Valor,” said Nielsen Esports managing director Nicole Pike, referencing the international title for Honor of Kings.

Following mobile esports is more popular in China than other markets, Pike said, which has helped naturally build up a relatively large female fan base.

Questmobile data also shows that, outside of messaging, Chinese female netizens under 19 spend more time on MOBA games than other mobile apps. Among women ages 19 to 29, MOBA games rank third.

How mainstream esports are in a country also affects the gender balance. There’s a direct correlation between esports popularity and how likely females are to participate, Pike said.

As the popularity of esports has grown in China, so too have the country’s championship titles. In 2018 alone, Chinese teams swept the international championships for League of Legends, Hearthstone and PUBG. Chinese teams also ranked highly last year in other games, including Overwatch and DOTA 2.

“The development of esports in recent years has made many people in our parents’ generation change their attitude,” said Chen. This has resulted in less pressure on women who have decided to pursue a career in esports.

However, the growing ranks of female fans doesn’t necessarily translate to an equal growth in the number of professional female players.

“Talented female players might rather be streamers instead of going pro,” said Chen. “You earn much more and there’s less pressure.”

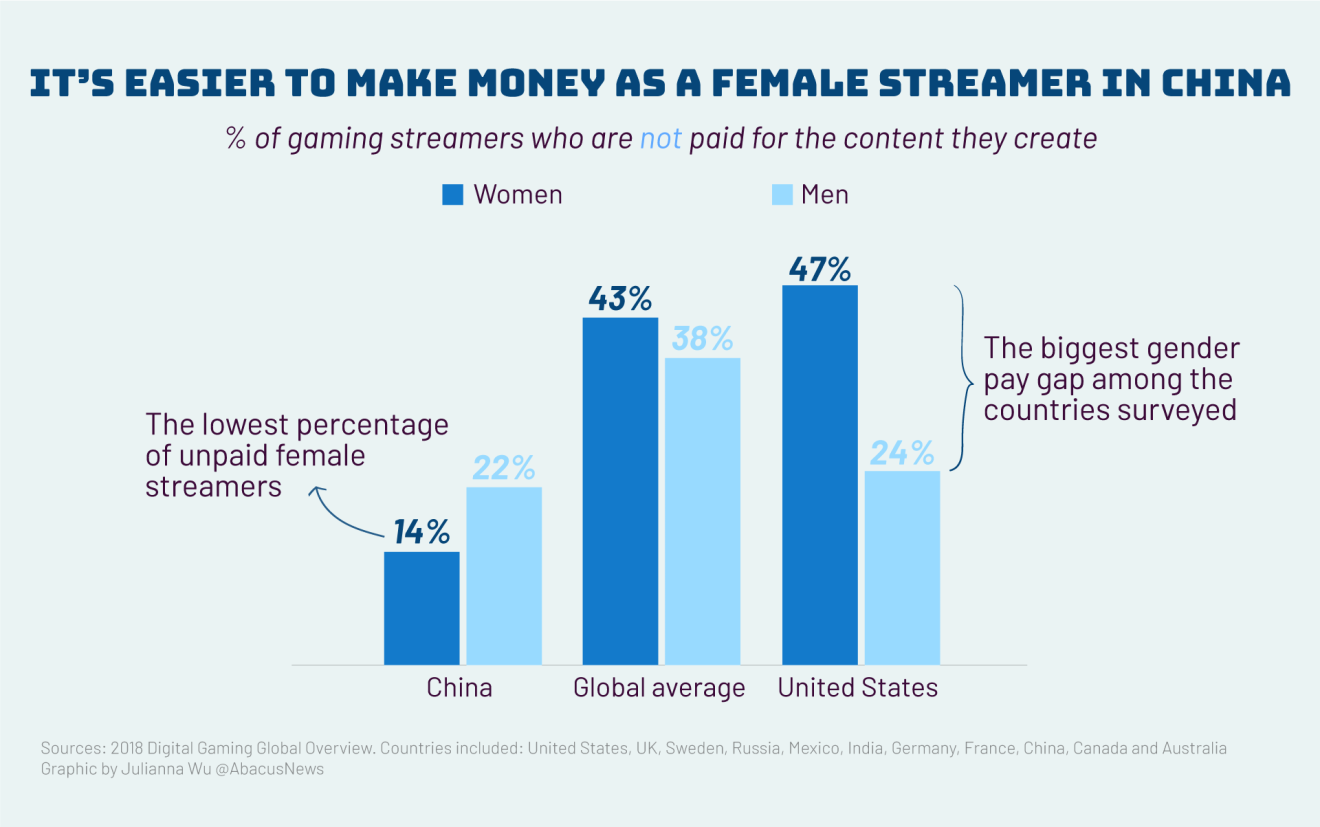

In fact, China has the lowest unpaid rates for male and female streamers, according to a report from PayPal and SuperData. It’s also one of just three countries where women are more likely to be paid for streaming than men.

LGD Girls, the women’s team for China’s famous LGD Gaming organization, says streaming is the team’s main source of revenue. “We stream four hours everyday, six days a week,” said team manager Kaidi Tu.

Chen moved on from playing League of Legends competitively for LGD Girls in 2018, when she started hosting tournaments. It’s very hard to be a professional gamer as a woman, she said, and the male gaze may be partly to blame.

“People always care more about your appearance first, whereas for men, there are much fewer comments on how they look,” she said.

There’s also the added difficulty that there’s no official female tournaments for many esports games, which Chen finds discouraging. “If girls don’t get their own platforms to show what they can do, they won’t be able to hold on for very long,” she said.

The outflow of talent is one of the biggest concerns for women teams, Tu said. Last year, the club had to rebuild a new female team for PUBG because their previous League of Legend team fell apart following a number of player departures.

Nara was part of that exodus. She now hosts tournaments for LPL, the biggest League of Legends league in China.

“I used to dream about the big stage of the LPL tournament when I was a pro player,” Chen said. “Now I can get on the stage as a host, and it still feels awesome.”